I’ve mentioned Matt many times throughout this story, but I’ve never revealed just what he meant to me. Around the age of twelve, I began to notice him and he began to notice me as an individual separate from his sisters. Up till then we were always referred to as “the girls”. Now he started to appreciate my love of music, my literary bent, my desire for his attention. Together we watched Jeopardy on TV and he was impressed with how many answers I got right. We would stay up late and watch the Dick Cavett show and laugh at Dick’s sardonic wit. (Also, Dick had the coolest guests.) Matt enjoyed my adoration, I’m sure, but his family was similar to mine in this, that he just didn’t know how to converse with me, nor I with him.

The years passed and I felt more and more attraction to him. I would dress with him in mind, and when he went away to medical school I had my first big “letdown” realizing that there was no guy who cared how I dressed. He had brought me a ring carved from tortoise shell when he visited Palau, and I wore it non-stop until college. The night he was packing to leave for Houston, where he would study with Dr. DeBakey, I sat up with him and watched him pack, but still we didn’t know how to break through the silence and really speak to each other.

When my dad died on July 10, 1969, it was less than a month before my sixteenth birthday. I was still an unrepentant sneak, in my hunger to know more about people and their lives, and a few days later I saw Matt’s journal open to that date, lying on his desk. I read, “Life is short, uncertain and every thing is temporary except people and God. The clichés are true but sometimes they seem more real. I love Gwen, and know that the Lord will give her an extra piece of his comfort. Because of Jesus we share our lives with each other and I am glad that part of my life is shared with Gwen. When people go to God, He gives them glory and he also gives peace to those who are waiting to make that trip.” My heart nearly stopped, to read those words, “I love Gwen.” It was such a strange role for me, being sort of like a sister to him and yet not.

How on earth was I able to reproduce that quote in its entirety? Yesterday, I found that page — I had ripped it from Matt’s journal. I can’t believe I did that! It was bad enough that I was sneaking around in his room and reading what he wrote. Okay, people, I am just as appalled as you are.

The books I would find in Matt’s room often had a transforming effect on my life. That’s where I discovered John and Elizabeth Sherrill’s They Speak with Other Tongues, which weakened my denominational ties His bookshelf was the source of My People is the Enemy by William Stringfellow, which politicized my spiritual thinking and opened my eyes to the complex tragedy of life in the ghettoes. Matt’s room is where I happened upon Salinger’s Franny and Zooey, which challenged my view of God.

Another book of Matt’s opened my eyes to the poetry in the world of nature. I already loved the mountains and had spent a lot of time at the beach over the years, but somehow having this book in my hands enriched and deepened my appreciation. Published by the Sierra Club, On the Loose by Terry and Renny Russell stimulated my wanderlust and epitomized the discoveries many in my generation were making about the world around us. I don’t think the book used the word “environment” even once, but it was a wellspring of environmental fervor.

I could hardly believe my eyes when I came upon a copy of this book in Elder’s Used Bookstore not long ago. It took me instantly back to my fourteen-year-old self. I had drunk in that book so deeply that I recognized nearly every page. The whole book was written in his own calligraphy, and Terry Russell accompanied their wonderful photographs taken all over the country with selected quotes from many authors. He didn’t attribute this piece to anyone, so perhaps he wrote it.

So Man is not what he appears.

I had been blind a thousand years.

Wisdom older than the seers

Beauty much too deep for tears,

And holy silence bursts the ears.

Ssh. The music of the spheres.

At one point, Matt was dating a college girl named Margaret Rose, and I was so jealous of her greater age and great looks. But standing in the kitchen, with her right there beside him, he asked me, “You’ll be here when I get back?” and found me after he had walked her home to her dorm. Another time, he had returned from Houston, saw me on the campus and came running, jumping over a bench, to give me a hello hug. These were confusing times. I wrote many poems to and about Matt, but I’ll just add one here that tells a lot of my heart.

You’ve given me so much.

Not always because you chose to

(in fact, direct and conscious

sharing was rare)

but in random phrases, shared music,

the mutual though separate strivings

with others’ words and our own

your self has made me rich

With you as my point of reference

I’ve reached out to discover

So much that’s part of me.

I’m grateful for this special and

Unusual relationship

And, though I pray for change,

I feel very strongly the comforting,

Exciting,

Confusing reality

Of now.

Matt loved God. He was a spiritual leader on campus and in the Campus Evangelism movement. His best friend Danny Jackson went into the Army following college, and Matt went to Europe to visit him where he was stationed with the Army Band. (Danny played some instrument in the band through his military service – a cushy job.) When Matt returned from that trip to Europe, something inside him had shifted. He had gone deeper into his pursuit of the hip world his music research had always represented. He had probably lost his virginity, if he hadn’t before, and started to play with drugs and drinking. At any rate, I don’t know if he ever returned to the innocence of his faith, and years later I had reason to thank God that I didn’t end up with him, as I’d dreamed of doing for so many years.

To my best friend in high school, Barbara Rueckert, I wrote the following confession. “Before, I admired him immensely but I was proud of myself enough to believe that something was possible. Now I have a better perspective of the situation and yet I idealize him more than ever. He is terribly involved, committed, sensitive – but adjectives don’t work, he’s more than any adjective. He appreciates so many things I do (unbelievable); I’m very jealous of him because he is associated with so many people (closely) and not with me. My selfishness just made me lose another chance to be with him. I need the security of his whole love before I can keep from being jealous when he loves and is loved by other people. I cannot be my real self with him. I am anxious to impress. I do not love him. (Hard to say.) I do not know how to love him and get myself out of the way. Oh boy, am I infatuated. Why do I have to know so much about him (the journals – pain, blech). What do I do? I do not understand what it is to be loved.”

Matt didn’t get into medical school the first time he applied, so he went to USC for a Masters in Public Health while he waited for the next year’s application process. For one of his classes at USC he undertook a photography project. He wandered around the streets and alleys of downtown L.A., capturing images of garbage and vagrants and those we now refer to as “the homeless.” Drunks and prostitutes and people who slept in parks became his companions that year.

I wrote something to Matt that sounded a lot bolder than I was actually prepared to be, with him or anybody. Of course, I never gave it to him. Maybe he was actually present, at Mary Lou Knight’s house, where I wrote this “one spacey night” (as I noted on the page, below the poem).

I can’t be honest with you, can I baby?

Can’t say what I’m feeling tonight

Can’t say how I want you

Can’t say how when your eyes get bright

with that holy tender look of light

for somebody else, how it hurts me bad

oh baby.

To you, I’m so good and so precious

I can’t be me and want you too

Now can I? But that special music

I’ve been saving has your name

written deep inside it and I want

to give it to only you

Won’t you take it, now please,

oh baby?

When Matt went on to Houston the following year, the pressures of medical school had him by day, and the lush life of the music clubs had him by night. He turned me on to Townes van Zandt and John Hiatt from his Houston clubs. The last thing I ever saw that Matt wrote sounded like it could have been written for our relationship.

This time the dust has settled

The people we’ve been

see it’s time to leave

and

we just got too old

to say hello

and nothing more.

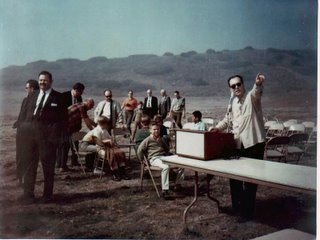

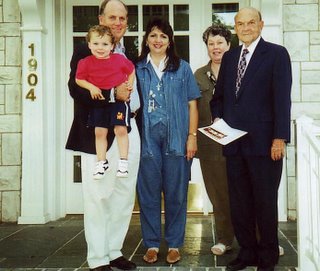

This picture was taken a few years later, on a canoe trip in the Malibu lagoon. Matt is on the left, then Norvel (his dad), then Amy and David Lemley (his niece and nephew), Marilyn in the green shirt, and Caren Hauser (you'll meet her later) helping David into the canoe.

This picture was taken a few years later, on a canoe trip in the Malibu lagoon. Matt is on the left, then Norvel (his dad), then Amy and David Lemley (his niece and nephew), Marilyn in the green shirt, and Caren Hauser (you'll meet her later) helping David into the canoe.Stephen Bennett’s name has come up several times now. How did he enter our lives? And why would a college guy choose to hang out with three teenage girls? Well, our attention and worship could have played a role in that. I had a major crush on Stephen, and unlike Matt, Stephen actually spoke to me. He and Marilyn really had more of a flirting thing going on, but he spent time with all three of us together. He had come to Pepperdine as a freshman that year, and his older brother Kenny was already there. His mother had been involved with Helen Young in one of the Northern California branches of Associated Women for Pepperdine, so he knew who the Youngs were by reputation before he arrived.

The same summer he took us to see the Supremes, he discovered I had never learned to ride a bike. I had tried. I had a bike with training wheels, but when they came off I couldn’t seem to dare falling. Stephen made me want to learn how to ride, to please him. He was appalled that I was thirteen years old and couldn’t ride a bike and he worked with me until I could. It was pretty funny and pretty bloody, with me crashing into the black iron fences that enclosed the Youngs’ yard because he’d forgotten to teach me how to brake.

At the first Campus Evangelism Seminar we went to, when Sara and I were thirteen and Marilyn was fourteen, Stephen hooked up with us and we went street witnessing together. (That was my first and last experience.) He and I talked to a bum for quite a long time, and Stephen finally determined that the guy was too wasted to serve as a significant evangelistic opportunity.

When the seminar was over, Stephen and Sam Jackson and Sara and Marilyn and I began meeting together as a “prayer group”, and Stephen ran it. It was the first time I had been in a small group where we shared personal moments from our lives. One communication exercise we did was to answer three questions of increasing intimacy.

1. What was the source of heat in your home?

2. What was the warmest place in your home, where people gathered?

3. What was one of the warmest moments you shared in your family?

We also started going together to Bible studies at peoples’ homes. This was a novel thing in my life, people sitting around a living room talking about God and Jesus, the Holy Spirit and the Bible in normal conversation, praying spontaneously, singing spontaneously, nothing planned ahead of time, no agenda, no one in particular leading. I grew so safe in that atmosphere that one night I fell asleep on the floor. When I woke up and it was all still going on around me, I felt so good. It was like being a little kid, secure in a happy family for the first time. Of course, I was hooked.

Though it was understood that Sara and Marilyn were his primary focus, Stephen paid attention to me. Once he made me laugh so hard that I cried. I had never experienced that before, and it felt amazing to get such a release. We were sitting in the family room at the Youngs’ house, and he said, “One day, someone is going to fall head over heels in love with you, and that will be that.”

Stephen’s long blond hair always hung in his eyes. When I heard the Judy Collins song, “Hey, That’s No Way to Say Goodbye”, I thought of him. “I loved you in the morning, our kisses deep and warm, your hair upon the pillow like a sleepy golden storm…” I longed for intimate moments like that. But they didn’t come, not with him, not with anyone for what seemed a long, long time.

Stephen once took me on a little adventure, to his apartment near USC for lunch. I loved the white wood and glass of the kitchen cupboards and the funky decrepit building his apartment was in. I don’t recall the lunch but I do recall that it was my first glass of wine. Mateus rosé was popular at the time, and even though it’s a cheap wine I still have romantic associations for it because it was “my first.”

There were other Pepperdine guys besides Matt that I knew, was interested in, wanted to like me, but it was always Sara, first, and then Marilyn, who were attractive to guys as dates. I was always “just” a friend. Sara, Marilyn and Janie all went out with Paul Humphries, for example, but I did not. I still have a chart I constructed, just for the amazement of it, listing several girls in the middle and connecting them with lines to all the guys who had gone out with them. I entitled it “Peppytech’s Peyton Place”. It’s still amazing to see how much cross-pollination (more figuratively than literally, I think) was going on within such a small circle of acquaintances.

My dad had just died (July, 1969) and now, a couple of weeks later, it was going to be August 5th, my birthday. Sara must have told Sam that I was “sweet sixteen and never been kissed,” and he decided to remedy that. I’ve always thought it was a kind gesture, but I have to say it was far too brief a kiss to really count. After church one evening, he pulled me into a side hall and, behind a door, he gave me a loving smack.

I graduated high school without having had a date or going to a dance or even going out with a group of friends from school. I had always hoped that by the time I got to college, I would be able to find at least a few guys who were more attracted to personality and brains and didn’t let the physical lack of standard “cuteness” get in their way. So I had a little bit of hope as I approached those long-awaited college years. I thought that if it didn’t happen by my senior year, then I could begin to worry in earnest. This was my prayer that summer.

how much more can I grow

without someone

to teach me

and to know

of me?

Maybe I need at least

to blow it.

I made a list of “Likes and Dislikes” sometime in high school. It was probably for some class because at the bottom I wrote “Cannot explain likes and dislikes” which sounds to me like something a teacher said, with which I would tend to differ. I always think you can explain everything – even if only to a degree. These haven’t changed over the years, except that I haven’t found any good sweet and sour pork since I left L.A. I opt for chicken now instead.

Likes

1. Stephen – sensitive & beautiful

2. brown wool – warm & strong

3. velveteen – luxury

4. fur – soft & cuddly

5. sweet & sour pork

6. badminton – power

7. long blonde hair – silky

8. Sam – unassuming

9. Dwight – strong

10. Paul – intelligent & funny

11. cold water – refreshing

12. milk & graham crackers – soft & squishy

13. fog & rain – comforting

14. beach at night – peaceful yet powerful

Dislikes

1. spinach – slimy*

2. hot sand – burns

3. squeaks & scrapings – irritating

4. lumpy gravy – lumpy!

5. Lawrence Welk – obsequious

6. Mr. Olechno – cold

7. dust – gritty

8. humidity – uncomfortable

9. gnats & mosquitoes – itchy

10. knockwurst & sausage – too strong

11. sarcasm with no love – inhuman

* I didn’t know yet that this was my mother’s fault because she added cornstarch. I like spinach and mustard greens and collard greens now that I’ve tasted them cooked the Southern way, omitting the added slime.

Sometime in that senior year of high school, Mom and I were still living in the Gray House together. We were in Daddy’s study next to the living room having a conversation about children and how they can disappoint you. Chip, who had been voted Outstanding Senior Man at Pepperdine, had married a Church of Christ girl like he was supposed to, had volunteered to join the Peace Corps to do good for other people, and seemed to me a paragon of virtue. I pointed to him as an example. “You can be proud of Chip, can’t you? You know he won't disappoint you, don't you?”

“I still don’t know how he’s going to turn out,” she answered.

I should have made a decision right then to cease ever seeking her approval . . . but, sadly, I didn’t.

Now the day came that I had been anticipating since Kindergarten. I was legitimately on the Pepperdine campus as a student, rather than as a precocious child. I had moved away from Mom and the Gray House into Marilyn Hall, the Pepperdine girls’ dorm, and what a fun move that was. I had the opportunity to do so much more socially. Out on the campus in front of the girls’ dorm, guys like Dan Garrett and Jeff Lombardo would be messing around, and they were willing to pitch baseball to me. Dan was actually on the college team, and since I felt he believed I could hit that ball…I did.

Now the day came that I had been anticipating since Kindergarten. I was legitimately on the Pepperdine campus as a student, rather than as a precocious child. I had moved away from Mom and the Gray House into Marilyn Hall, the Pepperdine girls’ dorm, and what a fun move that was. I had the opportunity to do so much more socially. Out on the campus in front of the girls’ dorm, guys like Dan Garrett and Jeff Lombardo would be messing around, and they were willing to pitch baseball to me. Dan was actually on the college team, and since I felt he believed I could hit that ball…I did.

When Jeff, who was not a pro ball player, would pitch to me, he would yell and harass me and I felt as if he were daring me to hit – and I couldn’t. I figured he must have coached his little brothers like that, and it may have worked for boys, but his style just didn’t work with me. The difference in my performance between Dan’s belief and Jeff’s daring me taught me something powerful about my motivation, which has helped me understand myself a whole lot better in other challenging situations.

Since I found out that I loved baseball so much, I acquired an old baseball from somebody (it had “George Jump” written on it), and an old worn glove, and I bought a bat. One day, a group of Asian students I didn’t know asked me to borrow my equipment. Then later they wouldn’t give it back! I couldn’t believe it. I gave up without trying to do anything about them. I simply had no idea how to get back what belonged to me.

One morning near dawn, I suddenly found myself standing in the middle of my dorm room and didn’t even remember getting out of bed. There was a giant earthquake going on, and this particular dorm room made it extra dramatic because the whole front side of the room facing the Promenade was windows from ceiling to floor. Every pane was rattling, loudly. The corners of the room literally did not look square, everything was shifting so violently.

As soon as the rumbling subsided, I opened the windows to look out over the front door of the dorm and see if anything had happened to the campus. Just a moment or two later I saw Helen Young, in her bathrobe and carrying her purse over one arm, scurrying down their driveway toward the girls’ dorm to check on us and make sure we were all right. Helen has always demonstrated that kind of selfless concern for people. There may have been little she could actually do, but her gesture of love toward us has always stuck with me.

I got to know a special girl that year named Elaine Thomas. I discovered that her older brother Ted was a friend of Matt and Danny and Sam. I learned that her father, J. Harold, had been the preacher in the congregation at Bangor, Maine when my parents spent six weeks there in 1947. (They were intensively studying German before taking the boat over to Europe.) Sam and some of us went occasionally to the home of J. Harold Thomas and his wife Roxie for Bible studies. He was preaching at the Westchester Church of Christ. Their youngest, Elaine, was living in the same dorm I was, and I enjoyed spending a little time with her. She made a remark one day that became a useful tool in God’s hands as He worked with my heart.

I had told Elaine about a conversation I had with another girl in the dorm. This lovely dark beauty was a hippie who enjoyed hearing me talk about God and Jesus, but listened as if I were presenting just another alternative philosophy. Finally, I felt I had made no headway in helping her see the reality of God’s love. I showed Elaine a poem she had written, and Elaine commented simply, “She needs to feel the prints of the nails.” (You can find the quote she referred to in the Bible, John 20:25-28.)

I was stunned into silence. I realized at that moment that I too needed to “feel the prints of the nails.” I couldn’t fathom having such a real, normal, practical, every-day personal relationship with the living Jesus that such a statement could come out of my mouth. I was still living in my head. Though I had made a commitment in 1968 to Jesus as the Lord of my life, and I had been attending countless hours of prayer meetings and Bible studies in my search for a deeper relationship with Him, He still wasn’t as real to me as He apparently was to Elaine. I wanted Him to be, but I didn’t know what was wrong with me or what to do about it.

o ~ o ~ o ~ o ~ o

Now allow me to introduce you to another significant character in the story. It was the fall of my freshman year in college, and I went to another Campus Evangelism seminar, for the first time as a college student! Finally! I had attended them for so long as a too-young “honorary” participant, and now at last I was officially the right age. This seminar was held on the campus of the University of California at Santa Barbara. Rich and Sandy Dawson were there, already married and a few years older than me. Sam Jackson was there, and others I knew. I was getting settled in the dorm room where I would be staying, and it connected to the next bedroom by a shared bathroom. There was a girl in there, and she came into my room, and said, “You’re Gwen Moore, aren’t you?”That was a shock. “Yes, I am, how did you know?”

“Well, I’ve been getting to know Matt Young and Danny Jackson and I’ve noticed that you’re friends with them, and I thought you and I should get to know each other too. Matt told me he thinks you’re terrific.”

And so we meet Naomi Frances Harper. She was a very slight, dishwater blond who tended to wear braids, with a childlike face and a soft, high voice. I guess I knew almost from the start that she was a poet. It didn’t take her long to write a poem about me. She lived in the same dorm I did at Pepperdine, in the more modern part in back. (My room was directly over the front door of Marilyn Hall, which proved to be interesting when people wanted to throw water balloons at kissing couples below.) At any rate, here we were at this seminar and we were suitemates, so nothing could have been easier than to hang around together that weekend.

This picture contains a lot of history. Behind us is the Youngs' house, which is no more. There's my first car, the yellow Camaro which Daddy bought just before he died. Naomi's wearing a long "granny" dress which we did a lot in those days, and I'm in my first pair of jeans. Wow.

This picture contains a lot of history. Behind us is the Youngs' house, which is no more. There's my first car, the yellow Camaro which Daddy bought just before he died. Naomi's wearing a long "granny" dress which we did a lot in those days, and I'm in my first pair of jeans. Wow.

It turned out that a small community had formed without my knowledge, which included Danny Jackson, Matt Young, Sam Jackson, Naomi and a girl named Suzi Townsley. It was Suzi’s apartment where they often landed. They were several years older than me, sexually experienced (though largely upright, compared to the culture of the day), and had more years under their belt of making their own choices than I did. I was fresh out of the can, so I found their relative adulthood intimidating.

They once spent the night at Suzi’s apartment and were waking up to a Saturday morning together when Danny Jackson introduced Naomi to a record by Fred Neil (“The Dolphins”, “The Water is Wide”). I later read that Fred Neil taught some guitar licks to David Crosby when they were both in Greenwich Village. Later on, Danny Jackson also introduced me to some of Mahler’s symphonies, to Samuel Barber’s “Adagio for Strings”, and to a wonderfully subversive black and white movie with Jason Robards, A Thousand Clowns. Danny Blair and Naomi and I accompanied him one night to the $1 Movie down near MacArthur Park where it was playing. Naomi wrote a poem about it the next day, and when he read it, Danny Jackson said, “Geez, Naomi, it’s just a movie.” Danny Jackson was definitely an instigator, and I sensed he had gained some wisdom as well as some cynicism on his journey.

Naomi and I became best friends. Her roommate was Marcia Smiley, an older girl who later played a big role in my life as well. One night in their dorm room, Marcia introduced me to contemporary Christian music, by way of Andraé Crouch. It was the first black music I had ever heard that praised God, and I was in love with it! Needy me met needy Naomi, and for a long while, we traded getting our emotional needs met, and we tried to encourage, appreciate and uphold one another in our faith, in our art, and in our relationships.

There was a message box for each girl who lived in the dorm, and it was so exciting to know someone was thinking about me because they put a note in my box. I got notes from Naomi, from Matt, from Sam, and others. For the first time in my Pepperdine life, I felt like an individual person with actual relationships, no longer a tangential “friend” who was semi-invisible compared to the more attractive girls around me. No longer third or fourth choice at best, but someone people were seeing in her own right.

One very special part of freshman year was having a new relationship with Sam Jackson. We had known each other now for about four years, and he had always been very clearly Sara’s man. But now Sara had been shipped off to Nashville, to attend Lipscomb University for two years, and Marilyn and Janice had driven together to Texas, to be roommates at Abilene Christian University. It was the first time in my California life that I wasn’t the third member in a sister act.

Sam was amazingly good to me. He and I started having study dates on Tuesday mornings at 10:00. We would meet in the library and sit together and read. I enjoyed glancing at his blue eyes a lot, and I enjoyed having a friend who was a guy, and I enjoyed having someone I knew to hang with in this sort of scary freshman year thing. Sam gave me a gift that year. He said, “You’re a good woman. I can tell a good woman, and you’re a good woman.” What a heartwarming word to hear.

As Naomi and I both got to know Sam as an individual, and not just as “Sara’s boyfriend,” I came to appreciate just what an unusual character he was. I’ll spare you the poem Naomi wrote listing several of his endearing quirks (though I do have it, in case you’re interested, in the Appendix). One of those, at the time, was that Sam would wash but rarely comb his silky blond hair. I was truly amazed when I discovered a line from a favorite poet, Kenneth Patchen, which I copied into my journal: “Blessed is he whose hair is matted.”